On Saturday night at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, above glowing tables crowded with wine glasses, President Biden invoked Pavel Butorin’s wife Alsu Kurmasheva. It’s a name you may not have heard as much as Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, but Alsu is the other American journalist that Russia has detained as it wages an unjust war on Ukraine.

Pavel and I have talked several times this spring. I know that he runs the grim details of Alsu’s new life in a small prison cell over and over in his mind, and that he has been trying for months to get the U.S. State Department to designate her as “wrongfully detained,” as Evan is.

“I am beyond the point of telling myself what I should have done, what Alsu should have done,” Pavel told me from his base in Prague in early April. “Clearly going to Russia was a mistake. I can't rewind the tape.”

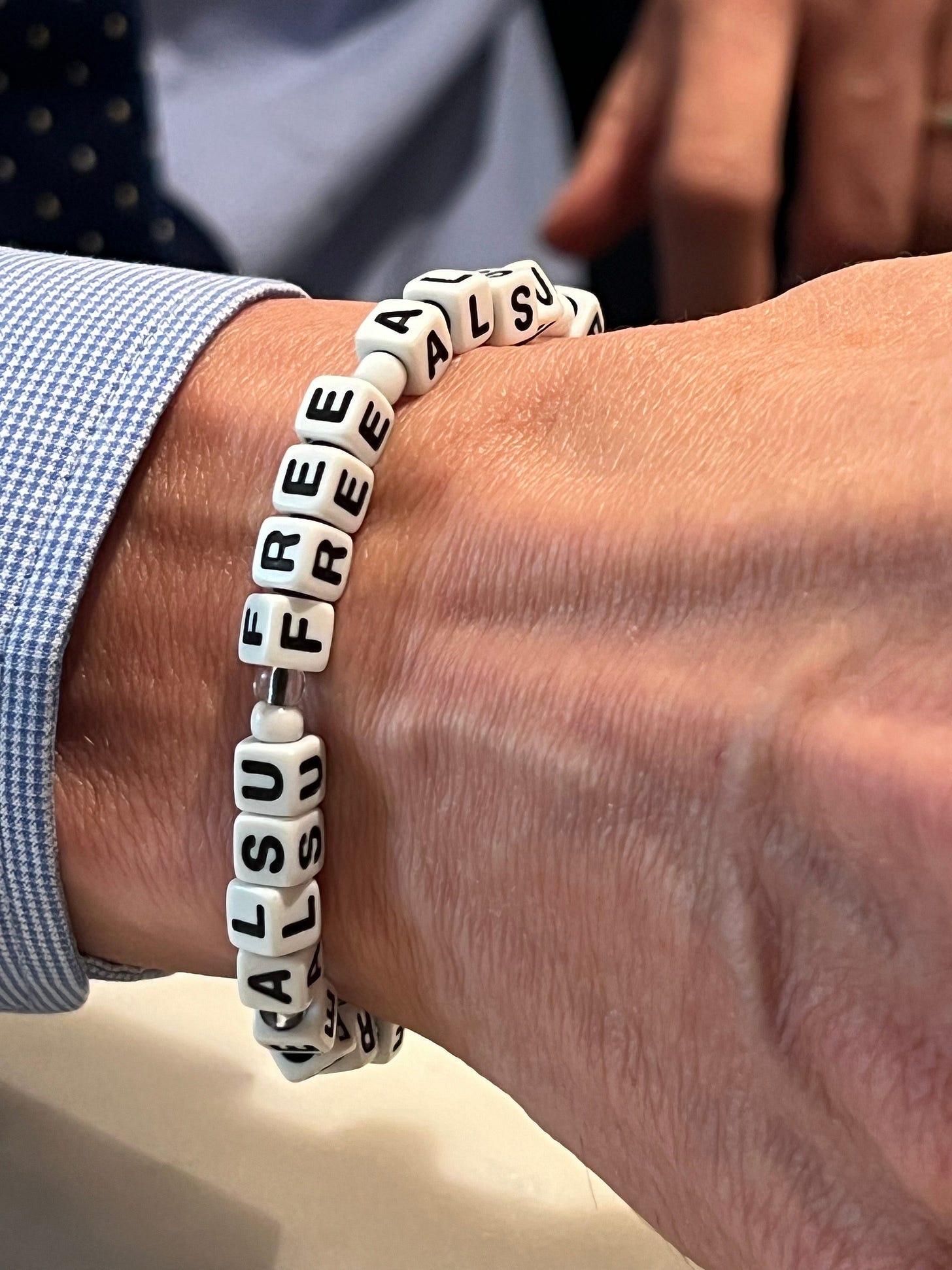

As we sit down to coffee in Washington, D.C., this week, he is wearing a suit and a beaded bracelet that says “FREE ALSU.” Their story begins about 20 years ago, at a birthday party where Pavel met Alsu, and she gave him a ride home in her Mazda. Now the life these two Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty journalists built is on hold. Pavel sees her in dreams at night. “Sometimes I see her on the tarmac,” he tells me. “Sometimes we're somewhere — the Grand Canyon — some places that we love in the United States.”

“Sometimes we're somewhere — the Grand Canyon — some places that we love in the United States.”

What follows is new information about Alsu’s capture and captivity, opaque dealings inside the U.S. State Department, what we know of FSB involvement, and how Pavel finds hope in the mess of it all.

Alsu’s arrest

Pavel hugged Alsu goodbye in May of 2023, not feeling the finality of it. Then she flew to Russia to care for her ailing mother, leaving behind not just Pavel, but their two daughters. Before she could board a plane back to them, the Russians took her cellphone and US and Russian passports. They questioned and released her, but held onto her documents so she couldn’t leave the country.

As the months went by, a $100 fine for failing to report her U.S. citizenship to the Russian government turned into an allegation that she was a so-called foreign agent. In October, she left Pavel a voicemail saying that the Russians were taking her away. Now, she lives in a small cell on a floor with enemies of the state, with a hole in the ground for a toilet. She has likely been under surveillance at the prison. She has been denied phone calls to her family, and has missed every family member’s birthday.

Ironies and disinformation weaponized

Alsu is detained in Tatarstan, and some of the judges and investigators involved in her case probably grew up listening to her voice on the radio some 25 years ago, speaking in her native Tatar language, Pavel tells me. Meanwhile, the Russian lawyers representing her in court fear for their own lives and families. They also had to sign non-disclosure agreements, making the details of her case unclear. But parts of the case have been leaked to pro-Russian media.

A purported “disinformation case” hinges on Alsu helping to distribute a book she edited called “Saying No To War.” It features 40 Russians who oppose Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia’s “evidence” comes from her WhatsApp messages, in which she and Pavel discussed places to share the book…in the United States. The irony should not be lost on anyone: Russia seems to be accusing Alsu of “disinformation” because she — outside of Russia — edited and distributed opinions on a war that Russia for so long refused to call a war, which began on a false pretext invented by Putin.

Confusion at the U.S. State Department

The State Department plays an important role in hostage negotiations, but it wasn’t always like that. When Diane Foley’s son James was abducted in Syria in 2012, “our government chose not to negotiate,” Diane told me in years past. He was beheaded by ISIS two years later, and Diane said, “I was just appalled. I was angry.”

She channeled those emotions into purpose, pressuring the U.S. government to start taking responsibility for citizens who go abroad, and get taken by terrorists or nation states. Her efforts helped lead to the establishment of a key office inside the State Department, the Office of the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs (SPEHA). The catch? SPEHA can only get involved once a person is declared “wrongfully detained.”

In the course of working on this report, I learned that the head of that office, Special Envoy Roger Carstens, really wants to take on Alsu’s case, but Carsten’s desire is just not enough. Neither is the fact that Alsu ticks off many of the boxes for the “wrongfully detained” legal determination. As of now, her case is being handled by the State Department’s Bureau of Consular Affairs, which doesn’t have quite the same expertise. What’s more, the U.S. Embassy in Moscow has been denied multiple requests to visit Alsu. There is also talk inside the State Department that some don’t want the list of “wrongfully detained” to get too long, but that is “rumor intelligence” (RUMINT) that is totally unconfirmed. A spokesperson from Carsten’s office simply tells me that while they remain deeply concerned, “we won’t get ahead of the process. It’s a deliberative, fact-based process.”

Biden administration still fighting for Alsu

Whatever the holdup, Pavel was still obviously concerned. “I worry about why she isn't classified as wrongfully detained and what that means for her chances to come back. When I hear State Department officials say publicly that they're working to free those American citizens who have been determined to be wrongfully detained, now how am I supposed to understand those statements?” He is quick to say that the situation was caused by Russia, “but I think it's fair to also try to understand what the United States is doing for their own citizens.”

Today, I have learned that regardless of the determination, senior members of Biden’s administration are pushing the Russians for a deal that would see Alsu and Evan released. The circumstances of these negotiations are kept vague on purpose. No one wants to jeopardize the Americans’ release — even if it keeps family members in a grievous dark.

What we know of the involvement of Russia’s domestic security service the FSB

There is little doubt that Russia’s FSB is involved in Alsu’s case. Pavel says that because she is an American citizen, her case is controlled from Moscow. “And knowing that Russia essentially has one branch of government, that is, the executive branch and security apparatus, yes I think it's safe to assume that the case is controlled by the Russian security service, FSB.” Officers are very likely conducting interrogations in an attempt to widen the case against her. She faces up to 15 years in prison.

How Pavel goes on

Every two months, the Russian court extends Alsu’s detainment. I asked Pavel how he finds peace in the midst of such an unbearable time. “I find peace when I see my children, when I come back home from work, when we spend time together,” he says. “I have to take care of them. I have to be confident and strong in front of my children, and they're strong and confident in front of me, too. I rarely see them cry… I just think that we’ll come out of this a stronger family. And this gives me solace and some peace.”

Then we talked about hope, sometimes a gossamer substance. “Hope is all I have at this point,” he said. “Maybe, maybe… an act of kindness on the part of the Russian government.”