Almost a whole year has passed for the hostages confined largely to Gaza’s sinuous tunnels and terrorists. How many have managed to stay alive? Recently the bodies of six captives, including 23-year-old American-Israeli Hersh Goldberg-Polin, have been discovered in a tunnel in Rafah. Autopsies show they were shot at close range last Thursday or Friday morning, hours before the Israel Defense Forces discovered them on Saturday afternoon. Protesters have taken to the streets, clasping photos of the slain, demanding that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu prioritize the return of the remaining hostages, 101 people according to Israel’s count.

It’s a plea made more disturbing because Netanyahu has a personal history of bold hostage recovery. And I don’t mean when he authorized the release of more than 1,000 prisoners for Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, held for five years by Hamas until 2011. Or even when he stormed a hijacked plane, disguised as a technician, to save hostages in 1972. This is a story about his older brother — Lt. Col. Yoni Netanyahu. He led a famous rescue of 103 hostages, known as Operation Entebbe.

After a childhood divided between Israel and the U.S., and an education divided between Israel’s Army and Harvard University, Yoni went on to be a commander in an elite special forces unit in the IDF. The secretive Sayeret Matkal gathers intelligence, conducts reconnaissance behind enemy lines, and rescues hostages outside of Israel. Established in 1957, it has generated intrigue and comparisons to the British SAS, U.S. Navy SEALS, and Green Berets.

And Sayeret Matkal had its work cut out for itself on June 27, 1976, when Palestinian terrorists from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and German terrorists from the Red Army Faction hijacked an Air France flight that took off from Tel Aviv. The plane never reached its final destination of Paris. Instead, the terrorists diverted the plane to the Entebbe International Airport in Uganda, where they were joined by soldiers under the control of the notorious dictator Idi Amin.

The terrorists began parsing out passengers, releasing travelers who weren’t Jewish or Israeli. Among the 106 hostages held in that airport terminal, some had previously survived the Holocaust. And Amin visited them, playing intermediator.

Just like today, the friends and families of hostages protested, calling for Israel to give into the hijackers’ demands so that their loved ones would be returned alive. Israel said it would negotiate, providing cover and a bit of time for a rescue operation.

In a 2012 documentary called Follow Me: The Yoni Netanyahu Story, former IDF officials and Sayeret Matkal commandos described an operation hashed together in a chaotic 48 hours. They rethought an initial plan of taking over the whole airport, opting to focus on the terminal (“like a bank robbery, we are going only to the safe”). They watched films of Entebbe and Amin’s army to select their clothing and vehicles. When they took off from Sharm el-Sheikh, an Egyptian resort town, the Israeli prime minister was still debating whether to approve the operation. It was nearly midnight as they approached Entebbe on a low flying Hercules jet, in the midst of a thunderstorm.

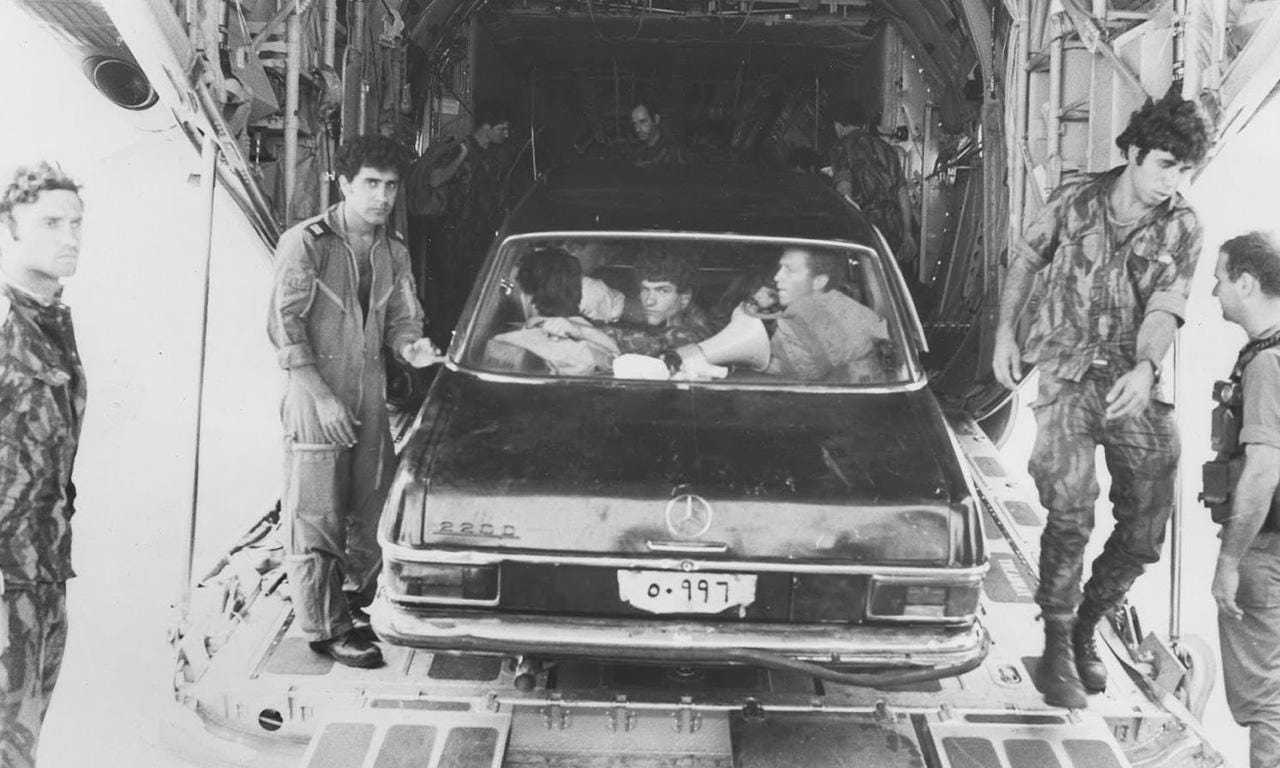

The commandos came out wearing Ugandan uniforms, driving two jeeps and a black Mercedes, nearly identical to Amin’s ride. It was a sight that fooled the Ugandan soldiers, allowing the Israelis to get closer to the airport terminal before a shootout began. The entire operation was said to have taken less than an hour. Killing the hijackers and troops supporting them, the squad rescued 103 hostages. Three hostages died in the operation. And so did Yoni Netanyahu.

Benjamin Netanyahu was just 26. The following year, he and his younger brother Iddo collected Yoni’s letters and published them in a book, the English-language version called The Letters of Jonathan Netanyahu.

“What kind of God-forsaken world are we living in?” Yoni wrote in one letter. “It contains so much beauty, so much grandeur and nobility, but men destroy everything that is beautiful in the world.”

Researchers at Ben-Gurion University have since analyzed the book’s 261 letters. They concluded that Yoni suffered emotional distress masked by superb functioning. They said he appeared to have, among other things, profound loneliness and “compulsive purposefulness.” The latter involves “a keen vision” between right and wrong, good versus bad, and how to handle adversity. It can sometimes lead to “a built-in mental frustration as there appears to be a constant gap between reality and ideology.”

How much did Bibi learn from his brother? What lessons did he take away from Operation Entebbe, and in the value of retrieving hostages from terrorists? Of course Israel needed to go after Hamas in the wake of Oct. 7. But is a potential gap between reality and ideology, in Bibi’s unrelenting quest to eliminate terrorists that threaten Israel, hindering him from hostage negotiation?

Like Yoni, Bibi had served in Sayeret Matkal and rescued hostages. After leaving the military, he worked for Boston Consulting Group, then became deputy chief of mission at Israel’s embassy in Washington, followed by Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations. Then it was onto parliament, and so began his career in politics. Some believe he got there on his own. Others think he used his brother’s legacy to launch himself.

I asked ret. Maj. Gen. Yaakov Amidror, a former advisor to Benjamin Netanyahu who still talks to him, if Yoni had an influence on Bibi. “I don’t know, probably no one knows, even he himself,” he told me.

But Chuck Freilich, the former deputy national security advisor to Israeli Prime Ministers Ehud Barak and Ariel Sharon, took a more definitive stance. “Clearly Bibi is not that concerned,” he said. “I mean, I don't want to deny him human emotions. I'm sure he cares about his brother and his legacy. But it's also pretty clear that Bibi is putting his own personal, political, and legal considerations ahead of the hostages.”

For years, Israel’s longest serving prime minister has faced charges of fraud, bribery, and breach of trust in three separate cases. He has tried to overhaul the judicial system and tried to delay testimony in court, pointing in part to the war in Gaza.

In the years preceding Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack and Israel’s war on the Palestinian enclave, Bibi attended annual memorials for Yoni, visited the site at the airport where his brother was killed, and joined a ceremony for an academy named after his brother.

“Undoubtedly, the most powerful experience in my life was the fall of my older brother Jonathan, Yoni, in the Entebbe rescue mission,” Bibi said in a 2011 interview. “And he died in the rescue and that changed my life, steered it to its present course because Yoni fell in the battle against terrorism, but he never believed that the battle against terrorism was only military. He believed it was political and moral.”

He went on to say, “When I go to a bereaved family in Israel, and I see a mother grieving for her son, I say, that's my mother. Or I see a father grieving for his son, I say, that's my father. When I see a brother, I say, that's me. And as a result of that I think carefully before I send our young men in harm's way. I have to, often, but I think about it. I think it makes me a more responsible leader.”

Those words were said in a different era. Today, 13 years later, some 340 military personnel have died fighting the war in the Gaza Strip, according the IDF. More than 40,000 Palestinians have been killed there, according to the Hamas-controlled Health Ministry. Israel and Hamas cannot come to terms on a ceasefire, each side blaming the other, over and over again, like a walk up and down M.C. Escher’s stairs.

Of course when it comes to the hostages, negotiations are arguably less risky than rescue operations. But the ultra-right, who string together Bibi’s coalition, want annihilation, not negotiation. “A deal will be extraordinarily painful for Israel, for everyone. That's going to require the release of huge numbers of convicted terrorists, people with lots and lots of Israeli blood on their hands,” Chuck says. The far right believe a deal equates to a short term benefit for a few, undermining the security of the nation.

Maybe Bibi prefers rescue operations, like the ones Yoni and he participated in. The IDF and Shin Bet have successfully brought back a few hostages that way. “It's a question of operational feasibility,” Chuck told me. “Any time the IDF comes and tells [Netanyahu], ‘There's an option to do it, we need the okay,’ I think he's giving the okay. And I'm sure he's encouraging them to go and look for this. And by the way, it makes him look good when there's a success.”

But success is in some ways harder to reach than the Entebbe airport. Even with radars, sensors, drones, and dogs. Estimates for the tunnels under Gaza range from 300 to 500 miles, with thousands of different shafts. One newly uncovered tunnel is said to be 25 stories deep.

About 11 months into captivity, the hostages have been treated in a way that defies Israel’s history, Chuck tells me. “Getting the release of one person was an overall national priority. It was part of the so-called social pact in Israel that you go, you serve, and you know that the country will do anything humanly possible to get you out.”

The failure to secure freedom has inevitably played into Hamas’ hand, even though Hamas is to be blamed for abducting them in the first place. “I think Hamas is doing whatever they can to exacerbate it through psychological warfare, selective release of signs of life, of videos of hostages, the killing of the six people last week,” he says. “It's all designed to exacerbate the domestic tensions in Israel.”

And so time ticks by for the hostages underground, while above ground the moral questions are debated.