My shards

Thanksgiving is upon us, spies and ordinary Americans alike. What do I have to be grateful for in 2024? I should be thinking about the people in my life, the immense opportunities this odd year gave me, the moments of joy that I searched for, found, and made. But for some reason, this year, I just keep looking at my things. The stuff I have collected over the years. What do I own and what does it say about me? And it turns out that beyond an impressive collection of plants in my Parisian-greenhouse-attic-vibe home, I have a lot of shards.

Glued to a plastic stand, I have a little piece of the Berlin Wall. I bought it when I lived in Berlin, my last stop before moving to Washington, D.C., where I write to you now. This shard has turquoise graffiti on it, sprayed at a time when the city was still divided. And of course we all know the wall fell — thanks to a communication mishap at a press conference in 1989. An East German official was supposed to announce some eased travel restrictions to quiet down protests. Instead, he mistakenly told reporters that East Germans were free to travel, effective immediately. Crowds rushed to the border, vastly outnumbering the unprepared guards. There was just no way to contain them. Hours later, they were flowing through the crossing, where at least 140 people lost their lives in incidents involving East German (GDR) border security. The Soviet Union would dissolve in 1991. But that day, people climbed the wall, sitting on it like a beast they collectively conquered, using picks and axes to whittle it down. And some of those chips would be sold to people like me. This shard brings me hope that life can get better.

I also have a shard of glass sharp enough to draw blood, and maybe the remnants did as they shattered. Because I pulled this shard out of the window of a bombed out Russian military vehicle in Ukraine this summer. Surely the last ride for the men who sat inside it. Based on the damage, there is no way they breathed another breath. And I don’t know why they went to war, if they were forced to or needed the salary or truly wanted to go after consuming a steady diet of Russian propaganda (you know, just a "special military operation"). As creepy as it sounds, every time I look at the glass shard, I think about dead Russians. Then I think of the bravery of the Ukrainians, defending their freedom, and the brutality of war. And I want to be reminded of that every day, even if it’s not my own story. Because it is easy to forget wars far away from you when they fall away from the headlines, when you don’t personally know the forces fighting, or when you may believe the war’s outcome will not affect you.

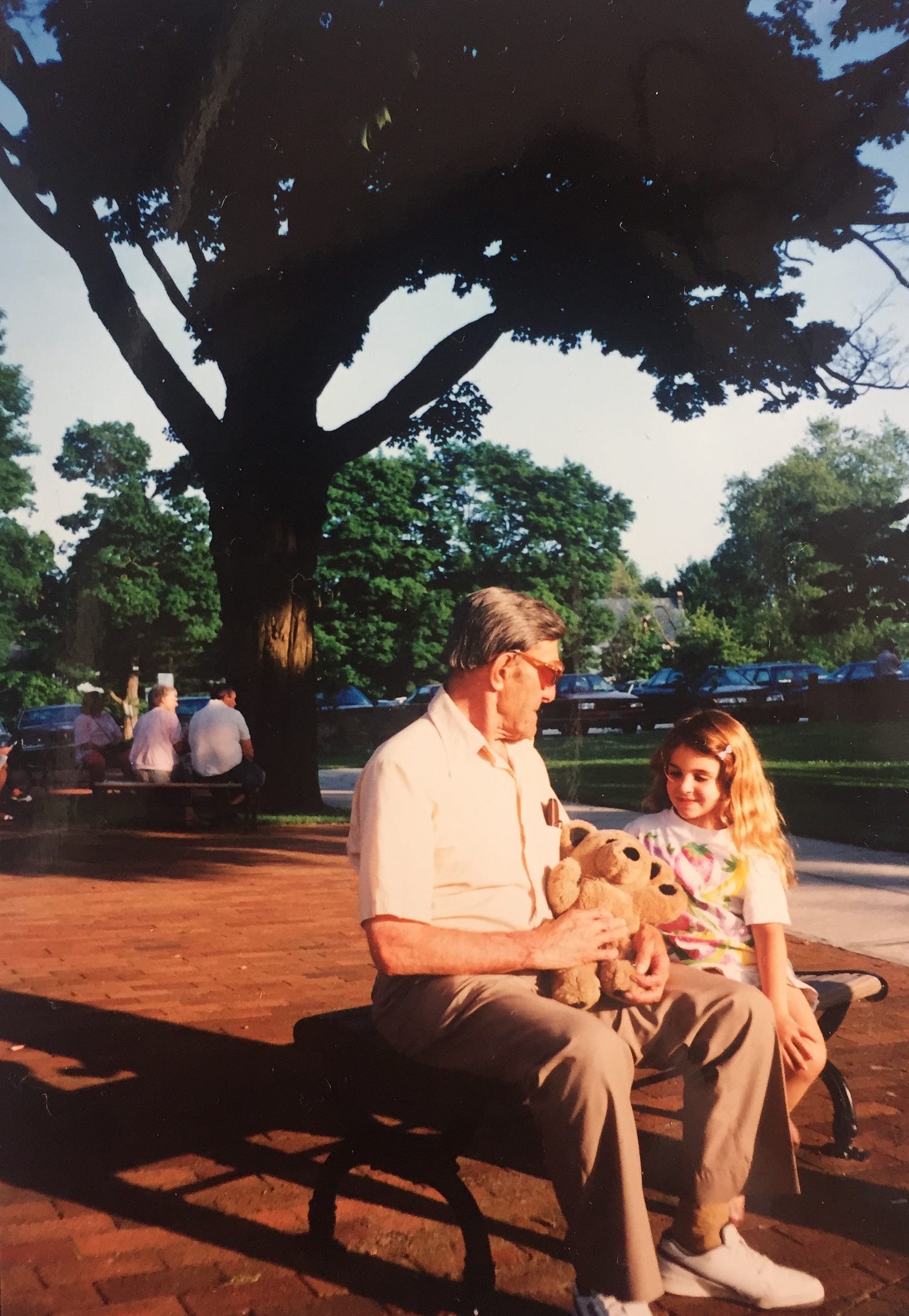

Two other shards come from the tiles at Buchenwald, one of the largest concentration camps that the Nazis built in central Germany. My grandfather was imprisoned there, severely beaten on his head, and experimented on. The doctors wanted to know how wounds responded to radiation. And I’ll tell you — because decades later, I watched my mother gently spread fresh bandaids over his bloody, hairless head for 12 years. The frequent exposure to x-rays caused a lot of skin cancer and sorrow. Sometimes he wore a wig to cover up the damage. He also indulged a girly girl, letting me paint his fingernails and play his padded fingertips like a piano, imitating the sounds of the keys as I laughed. I can’t remember the moment I learned about his imprisonment or the murder of so many members of my family. But I do remember him crying in his seat at a movie theater when we went to see Schindler’s List.

About 12 years after that, I was now a young woman living in Berlin, taking a train to Weimar, close to Buchenwald. I walked through the camp’s wrought iron gates, knowing that I could walk back out. Many of the structures were gone and the deep green hills in the distance could have fooled a person into believing these were the grounds of a sleep-away camp. I found Buchenwald’s medical ward and stood on the broken tiles, imagining my grandfather’s feet on the same floor. Were pleasantries said to mask the atrocities? I had to accept the history I had inherited. And I hoped that he had dared to imagine back then that his granddaughter would stand in the same spot decades later, in his memory. (How rare was optimism and imagination in such inhumane conditions? I didn’t know.) I picked up two loose shards, green and beige, and put them in my pocket. I needed to capture the pain of being there. I needed to hold onto it.

These brittle substances I found. These jagged fragments I take with me. It might sound random to read about them here, when you’re used to reading spy stories. And when I report, you wouldn’t have any idea they were beside me, living their inanimate lives, gathering dust and history. But I guess this year, I have been thinking about the pieces of my life, tangible and intangible. The messy, broken parts that may hurt, but still have beauty and meaning. I think it’s okay to look at them. Happy Thanksgiving, my reader friends.

I was very moved by both your ability to share your story and to express a deep heart felt pain and the connection to all of it. It’s a special brand of courage. Thank you, it’s another gift.

If I may, I would equate your collection of shards to some Native peoples who carry a medicine bag. The small items collected and stored in this sacred container represent connection, overcoming, and remind us of our deep inner power.

I have one and revisit it occasionally to find my own power in times of weakness.

Many thanks and good feelings for Thanksgiving.❤️🙏🏽🇺🇸

I loved this very personal and emotional reflection.