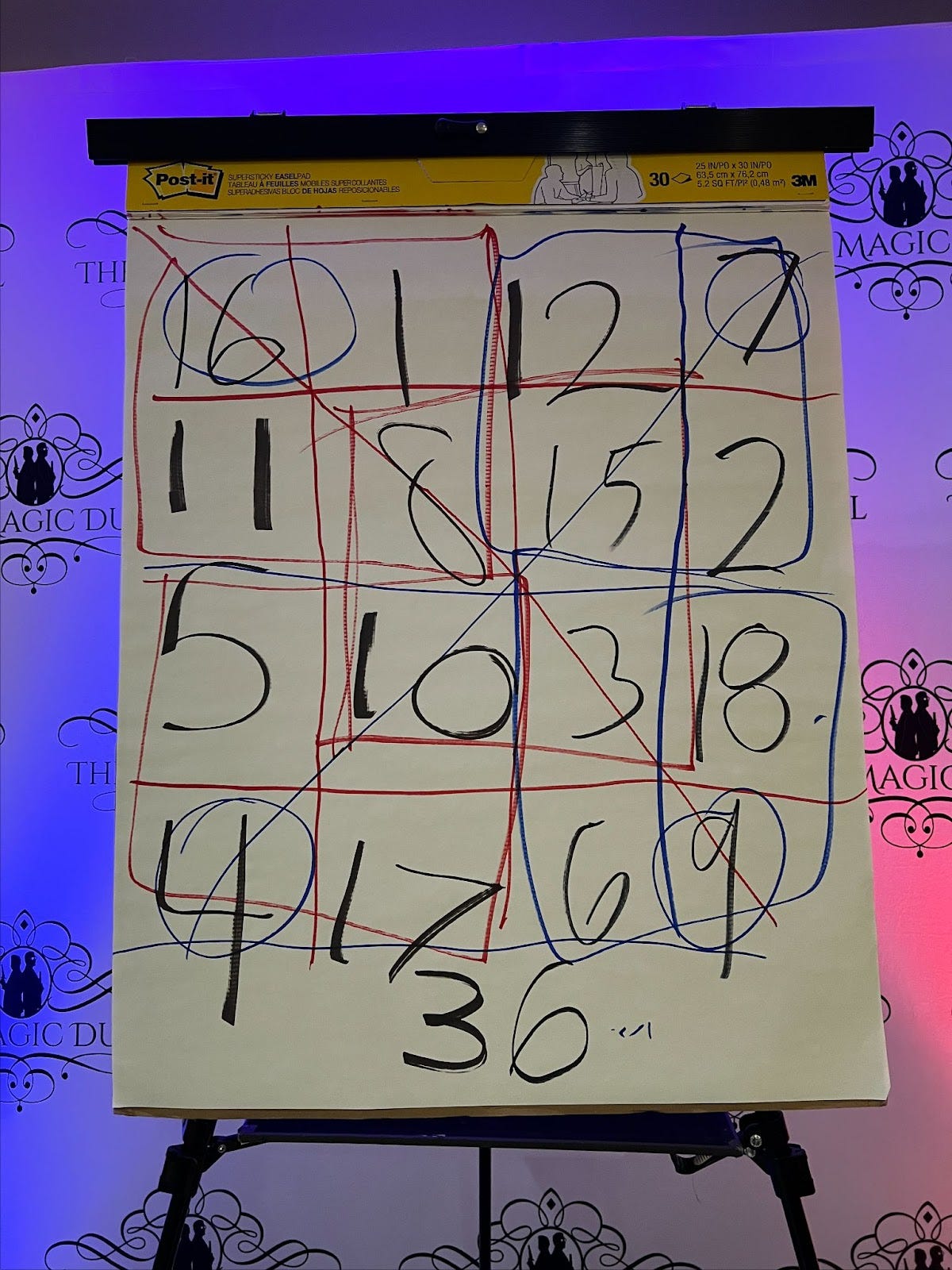

A few weeks ago, two magicians were dueling at a hotel in Washington, D.C., just as they always do. As part of the act, one guy held up some pieces of rope, changed their lengths in his hands, and then combined them into one single strand. Then the other guy came on stage and tried to one-up him. There were cheesy jokes, cards that magically appeared in participants’ pockets, and a plunger on a head for mind tricks. As a final performance, they joined forces, asking a volunteer to think of a number, say, between 20 and 50. A man in the audience chose, and the magicians tried to guess. They kept getting his number wrong, as they wrote down digits on a large pad. But then they asked the audience to look more closely at the grid they had drawn. In every direction, the numbers added up to the man’s chosen number -- 36.

Was the man part of the act? After the show, he told me he wasn’t. And if he was telling the truth, how did the trick work? Like a child greedy for answers, my eyes had been searching for clues during the show. Afterward, my friend and I turned to Chat GPT, knowing that Artificial Intelligence grows more capable by the day. We fed it the parameters of the trick and even the image at the top of this report.

What we discovered: the AI did not know magic. Instead, it gave a long-winded answer as a pedant would, elaborating on irrelevant minutiae without reaching any real point -- what is called a “hallucination,” when large language models generate inaccurate, false, or nonsensical responses. And in truth, I like to imagine a coterie of magicians still honoring their craft, keeping their slights of hand away from the public.

If magic tricks have not been leaked or hacked, the recipes for violence and destruction have. In a rare FBI briefing I attended last year, an official speaking on the condition of anonymity described how violent extremists and traditional terrorists are using AI to solicit ways to create different types of explosives and potentially lethal chemical and biological substances. Some have gone as far as to post about their successes with AI models, the official told me. And unsurprisingly, China has also been prioritizing ways to steal American AI technology and data, the FBI official said. It has been increasingly targeting and collecting on U.S. companies, universities, and government research facilities.

So what AI should not learn -- based on humans choosing to hold back information -- became a question I asked this week.

“I don't have any particular areas that I would say are absolutely forever to be forbidden from being used by AI,” says Chip Usher, the Senior Director for Intelligence at the Special Competitive Studies Project, a nonprofit organization that advises the intelligence community. He retired from the CIA about a year ago, after 32 years at the agency.

And yet, from an office in Crystal City, a hub for the defense industry in Arlington, V.A., Chip says there are some covert areas where relying on AI to recommend forces of action, including covert influence or kinetic action, “need to have a well thought out, thorough, human-in-the-loop type of guidance so that the IC does not rely solely on an AI to make some of those decisions.” (And CIA’s top brass have said humans take primacy, that AI will augment but not replace humans.)

Here are the areas where the intelligence community is cautious with or withholding information from generative AI, according to Chip:

Commercially available data on Americans that it considers to be sensitive. Because anything on the internet can essentially get sucked up, Chip says the IC is bringing algorithms on their high side (aka classified AI systems), experimenting in a “closed-off, sandbox type arena,” i.e. using smaller, in-house language models.

Information that could jeopardize sources and methods. Chip says the IC is working on ways to leverage cloud technology and cybersecurity to protect the digital breadcrumbs involved in conducting operations, while still taking advantage of AI.

Operational information that could end up leaking if it’s used in commercially available AI.

And how is the intelligence community using AI? It is largely to manage enormous datasets. That includes “computer vision,” which is used to detect objects in images, a source who works on government projects told me. In Ukraine, AI has been paired with drone footage, satellite images, and social media to provide intelligence on Russian forces, including their units, identities, movements, weapon systems, and morale.

AI is not new to the intelligence community. “The exact origins of their work on it probably are classified, but it goes back at least a decade,” Chip says. In those early days, that meant machine learning. The CIA made an investment in machine translation of foreign language material -- which not only sped up processing but has allowed the agency to be more strategic about who needs intensive language training.

The CIA’s new, unclassified generative AI tool, called Osiris, is available to all 18 intelligence agencies. “They're using it mainly for unclassified open source reporting,” Chip says. Osiris can summarize massive amounts of information, allowing analysts to quickly learn key points from dozens of articles, then ask follow-up questions to determine where they want to focus their time.

But the questions must be posed carefully, as U.S. adversaries want to know the queries too. Because of that, intelligence officers are trained on which queries they can use on the low side and high side.

Threats of foreign penetration only grow more stark in the AI age of intelligence, Chip tells me. “AI-enabled tools will allow our adversaries -- by the way, not just state actors but non-state groups like Hezbollah -- to use AI to uncover our undercover officers, or discover their travel, or understand what bank accounts they're using to pay agents. So we need to make our intelligence community AI-proof, even as at the same time, we're taking advantage of AI tools for offensive purposes. So that is, I think, going to be a big business area for the IC going forward -- how to deal with how our adversaries might use these systems against us.”

Chip also pointed me to a translation of a Mandarin-language article published in a Chinese military journal in March. It described AI’s importance in “algorithmic cognitive warfare,” what it describes as an invisible war: How AI can mine images and speeches of a target -- assessing keywords, intonations, and personality traits to assess emotions, stances, interpersonal relationships, and command chain; correlate content with military operations and social events; and analyze the enemy's algorithm to evaluate its technical level and attack range.

I asked him what China itself may be withholding from generative AI. Chip told me that Beijing has been taking publicly available data off the internet to protect the regime. “They've really put the clamps down on what foreign actors, non-Chinese actors, can access on the internet. And this is restricting how AI systems that are reliant on the internet could acquire information on what is happening in China.”

Something else could happen in the reverse, he says. China, Russia, or other U.S. adversaries may try to pollute American AI algorithms or data sets. “They can trash our AIs to make them useless while they use it themselves.”

As it is, Chip tells me the U.S. intelligence community is not on track to meet a two-year deadline set by the Special Competitiveness Studies Project for deploying generative AI at scale -- despite assertions by the CIA’s first Chief Technology Officer that “We think we’ve beaten the initial timeline by a big margin.” All of the intelligence agencies have designated an AI lead and are trying to stay ahead of the curve despite smaller agencies having fewer resources. But part of the holdup has been the White House, which has yet to produce a national security memorandum that will govern how the Department of Defense and the intelligence community use AI. An October 2023 executive order sets the deadline for 270 days, putting us at July 26.

“I worry not so much about today, but if we drag our feet for too long, I worry about where we'll be in another two years' time, because that technology is advancing that rapidly,” Chip says.

He says the spy games will evolve to include delivering “speed to insight.” Will the U.S. be faster (and more insightful) than China and Russia? It depends, he says. “Perhaps the IC won't be at the absolute forefront of what is technically possible, while it sorts through the critical policy and operational considerations that it has to take into account.”